Project Design

Introduction

The Project was developed through an iterative discussion process with researchers, government officials and communities. The approach has evolved during the course of the project, as it must, adjusting to the changing circumstances and the increased understanding of the conditions and opportunities faced.

Aims and Objectives

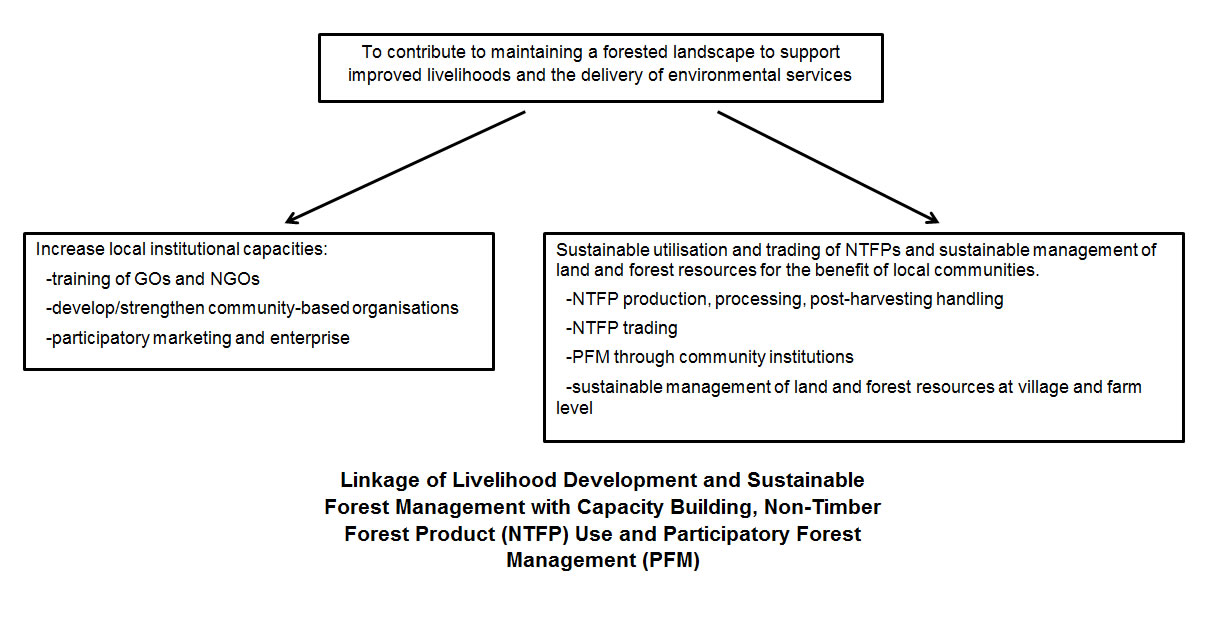

The NTFP-PFM Research and Development Project sought to develop ways of working with communities and government agencies in order to improve livelihoods and maintain the forested landscape and environmental services in the Kefa, Sheka and Bench-Maji Zones of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Regional State.

Critical to this work was the building of capacity in the government agencies operating at the field level and in local communities, with the development of community-based organisations (CBOs). The other element was the development of incentives for forest maintenance through the development of forest-based enterprises, especially the production of NTFPs and their sale.

This diagram shows the linkages of project aims and objectives:

Approach

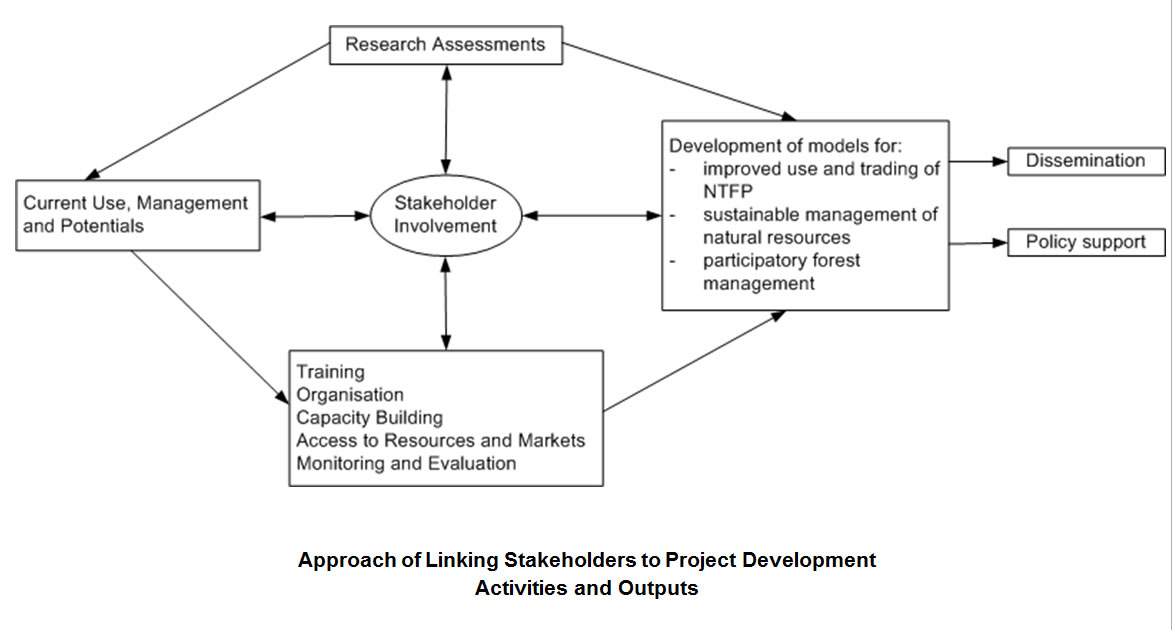

This NTFP-PFM Research and Development Project took a participatory approach; its activities being driven by various needs assessments and action research processes it undertook, as well as a participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation system which was established. The project focused on practical measures, exploring production, management, processing and marketing methods for NTFPs, and different ways and incentive systems to manage and protect the forest in a participatory manner, with community-based institutions.

In particular the project emphasised:

- Active stakeholder participation in all phases of project cycle;

- Promotion of communication links and exchange of information between stakeholders;

- Building on local knowledge and local institutions;

- Learning by doing;

- Farmer to farmer training;

- Facilitation of implementation by communities and government agencies.

Gender Issues

There are distinct variations in the involvement of women and men in NTFP collection, processing, sale and domestic use, as well as in the use of other forest products and in forest management. In general, women have less secure access to NTFPs and forest resources and although their labour inputs are often considerable they gain less income than men from the NTFPs that are sold.

The project identified these gender specific roles and helped women to identify ways in which they can generate increased benefits, domestic and cash, from forest products. Training women to develop activities empowered them and ensured their equal participation in all project activities.

The project found that women tend to collect forest products more for household use and sell surpluses only when time and resources allow. They tend to collect close to home and opportunistically, whilst men tend to undertake planned (long-distance) ‘collecting trips’. Men are more likely to be ‘specialists’; women tend to be ‘generalists’.

Women have few, if any, secure access rights to NTFPs, as their collecting activities and access vary more spatially and over time, while the products they collect are perceived to be of lower value compared to those collected by men. As a result, the NTFPs that women use tend to be unprotected and open to access (and exploitation) by all.

Men’s and women’s knowledge about natural resources, biodiversity and conservation is different because of their different relationships with the resources. Thus, it is important to make any decisions concerning intervention and/or activities on good in-depth understanding of local gender issues.

It is suggested that NTFPs represent an important source of income and employment, particularly for women. Support for increased NTFP gathering and production activities should recognise the diverse impacts of an increase in production and any negative impacts should be mitigated.

One feature common to many NTFP commercialisation programmes is an effort to improve processing technologies for a variety of reasons: to improve quality, to increase locally added value, or to increase product supply. Some studies of new technology introductions reveal a pattern whereby men displace women from NTFP processing. This is another potential issue to be considered.

The sale of NTFP may be one of the few opportunities women have for earning an income. Thus, the scope for NTFP-related activities should not be seen only as a means of boosting incomes, but also as a safety net for the poor (both men and women).

Community Participation

The NTFP-PFM Research and Development Project was driven by the needs of the communities and different stakeholder groups therein. In order to ensure that locally perceived needs were at the heart of the project's activities, extensive PRA studies were undertaken at the kebele (parish) and got (village) levels. Project planning was based on these PRA studies, and on an interactive participatory planning and discussion process between the project and communities which occurred on a regular basis to review project activities progress and plans. One formal element of this process was the Project Advisory Board which included stakeholders and representatives from all areas where the project worked, as well as all ethnic groups and government departments.

Community involvement was central to the project's capacity building focus. Throughout the project, the aim was to support and engage local actors in the project activities, and for the project staff not to be undertaking activities themselves. Hence the project worked with local community institutions to strengthen them; for instance, training NTFP producers, forest product harvesters and PFM groups in particular methods, advising on marketing strategies and management strategies, and helping interest groups form specific organisations to assist address their needs.